Refunding VAT paid abroad: how OSS affects input VAT recovery

Spis treści

Instead of being forced to register for VAT in every country where your customers live, the OSS allows you to declare all your cross-border sales in one place. You file a single quarterly return in what is called your Member State of identification. For EU-based sellers, this is usually the country where your business is established. After you submit the return and make the payment, your local tax authority forwards the VAT to the tax authorities of the other Member States where your customers are based.

For young e-commerce businesses, this system is a breakthrough. It reduces administrative stress, lowers compliance costs, and gives you a chance to expand into new markets without immediately drowning in paperwork. That is why the OSS has quickly become popular among entrepreneurs who want to grow across borders without dealing with multiple tax registrations.

Where confusion begins: expenses and foreign VAT

As every seller knows, business growth does not only bring sales but also expenses. You might buy stock from a supplier based in another Member State, pay for warehousing in a different country, or hire logistics partners abroad. Each of these transactions can come with VAT charged in the country where the purchase took place.

It is natural to assume that, since OSS already helps you handle VAT on your cross-border sales, it should also allow you to reclaim the VAT you have paid abroad. On paper, it feels like the logical “one-stop” solution that covers both sides of VAT: the output VAT you collect from your customers and the input VAT you pay on your own purchases. Many small e-commerce owners begin with exactly that expectation when they first sign up for OSS.

The reality: what OSS does not do

This is where the misunderstanding becomes clear. The OSS was never designed to handle input VAT. Its purpose is to simplify the declaration and payment of output VAT only — in other words, the tax you charge your customers. If you have paid VAT in another Member State when buying goods or services there, you cannot reclaim that amount through your OSS return.

To recover that money, you need to use a different route. Some businesses deduct the VAT through a local return in the Member State where the purchase happened, but that requires a local VAT registration. Others rely on the EU’s electronic VAT refund procedure under Directive 2008/9/EC, which is available for EU-based companies. Non-EU businesses, on the other hand, have to use the separate procedure under Directive 86/560/EEC, better known as the 13th Directive. Each of these approaches has its own requirements and deadlines, and choosing the right one depends on the way your company operates.

A crucial deadline to remember

One of the most important details, especially for EU businesses, is the deadline for filing a refund claim under the electronic refund procedure. You must submit your application through your home country’s tax portal by 30 September of the year following the refund period. Missing this deadline can result in losing the right to claim, which for a small or growing business can mean leaving significant amounts of money unrecovered.

Why this distinction matters

For young online sellers, this separation between output VAT handled by OSS and input VAT recovered through other procedures can feel frustrating. However, understanding it early on can save you from cash flow problems and ensure that you are not caught off guard by unexpected costs. The OSS is a powerful tool for simplifying compliance, but it does not replace the traditional mechanisms of recovering foreign VAT. Knowing exactly what it can and cannot do is the first step in building a tax strategy that supports your growth across Europe.

Understanding the OSS Scheme

From distance-selling thresholds to the OSS

Before the EU e-commerce package was introduced in July 2021, online sellers faced a patchwork of rules. Each Member State had its own distance-selling threshold, often set at either thirty-five thousand or one hundred thousand euros. Once a business exceeded the threshold for sales into a particular country, it had to register for VAT there, file returns locally, and charge local VAT. This meant that a growing online shop could easily find itself juggling five or six separate VAT numbers and multiple reporting schedules, creating both cost and confusion.

The OSS replaced these thresholds with a single EU-wide threshold of ten thousand euros, but only for businesses established in one Member State. Below that amount, sales can still be taxed in your home country unless you voluntarily opt into the OSS. For businesses selling at scale, opting in makes sense, because above the threshold all cross-border B2C sales must be reported under OSS or through local registrations.

What OSS actually covers

The scope of the OSS is limited to B2C transactions, which include intra-EU distance sales of goods and certain services supplied to consumers. The scheme allows sellers to consolidate their VAT reporting. Instead of dealing with each country separately, you file a quarterly return in your Member State of identification. This is usually the country where your business is established if you are EU-based.

The return covers all cross-border sales to consumers in other Member States. You apply the VAT rate of the customer’s country, report it in your OSS return, and pay a single consolidated amount. Your home tax authority then forwards the correct shares of VAT to the other Member States, ensuring each country gets its due.

This system works for most cross-border B2C activity, but there are exceptions. If you maintain a fixed establishment in another Member State — for example, a warehouse or fulfilment hub that creates a taxable presence — then your B2C supplies from that establishment are not covered by OSS. Instead, they must be reported through a local VAT registration in that country. This detail is often overlooked, but it is crucial for businesses using fulfilment centres across Europe.

Why OSS is limited to output VAT

The main attraction of the OSS is the simplicity it offers: one return and one payment every quarter rather than multiple registrations scattered across the EU. However, it is equally important to understand what the OSS does not do. It was designed exclusively for the declaration and payment of output VAT, meaning the VAT you collect from your customers.

It does not allow you to deduct or reclaim input VAT paid abroad. For example, if you buy stock from a supplier in Germany but your business is based in France, the German VAT you pay on that purchase cannot be offset in your French OSS return. To recover that money, you need to use other channels: a local VAT return in Germany if you are registered there, the EU electronic refund procedure under Directive 2008/9/EC if you are EU-based without a German VAT number, or the 13th Directive refund procedure if your business is established outside the EU.

Why the separation exists

From a business perspective, it might seem more efficient if OSS also covered input VAT. In practice, the EU deliberately kept the systems separate. Allowing deductions of foreign VAT inside the OSS would make it harder for tax authorities to audit claims, complicate control mechanisms, and open the door to fraud. By limiting OSS strictly to output VAT, Member States maintain control over refunds of VAT incurred on their own territory.

This separation can feel inconvenient, but it is the foundation of how the EU’s VAT system balances simplification with control. For sellers, the practical message is straightforward: OSS will streamline your sales reporting, but you must still use local returns or refund procedures for your expenses.

Why OSS does not cover input VAT

Output VAT versus input VAT

To understand why OSS cannot be used to reclaim expenses, it helps to separate two basic concepts. Output VAT is the tax you charge your customers when you make a sale. This is the tax OSS was created to simplify: a single quarterly return, a single payment, and your home tax authority redistributes the VAT to the Member States of consumption. Input VAT, by contrast, is the tax you pay on your own business expenses — such as stock, warehousing, logistics, or marketing services invoiced with VAT in another Member State.

The OSS return covers only output VAT. It contains no field, no mechanism, and no legal framework for recovering input VAT paid abroad. Even input VAT linked to OSS sales in your own country must still be claimed in the normal domestic VAT return of your Member State of identification, not through the OSS return itself.

Local rules remain in place for input VAT recovery

Because OSS does not touch input VAT, the rules for recovering it remain entirely with the individual Member States. If you pay VAT in another EU country, you can only reclaim it if you are registered there and deduct it through a local VAT return, or by using the EU’s refund procedures. For EU-based businesses, this is the electronic refund procedure under Directive 2008/9/EC. For non-EU businesses, it is the 13th Directive procedure under Directive 86/560/EEC.

In other words, OSS runs in parallel to these mechanisms but does not replace them. When you submit your quarterly OSS return, the foreign VAT you have paid on business expenses is irrelevant to that declaration. If you want that money back, you must use one of the separate recovery routes.

Why the EU kept OSS and input VAT separate

From the perspective of many online sellers, it might feel inefficient that OSS does not cover input VAT. After all, if the system already collects and redistributes VAT across the EU, why not also allow businesses to claim their refunds in the same place? The answer lies in the priorities of the tax authorities.

Refunds represent a cash outflow from governments to businesses, and they carry a higher risk of fraud than the collection of output VAT. By keeping input VAT recovery under the direct control of each Member State, tax administrations can apply their own rules, conduct audits, and ensure that only legitimate claims are paid. This design choice was deliberate: OSS was meant to simplify reporting of sales, not to centralise refunds.

The business takeaway

For businesses, the message is clear. OSS is a powerful sales reporting tool, but it is not an input VAT management tool. If you incur VAT abroad, you must plan to recover it through local registrations or refund procedures, entirely separate from your OSS compliance. Recognising this distinction early helps avoid confusion and prevents costly mistakes when forecasting VAT recovery.

Options for recovering foreign Input VAT

Once you understand that OSS cannot be used to reclaim VAT on your own purchases, the next question is obvious: what are the alternatives? The EU has kept the traditional routes for recovering foreign input VAT in place, and which one applies to you depends on how your business operates and where it is established.

Local VAT registration in the Member State of purchase

The most direct way to recover input VAT in another country is to register for VAT locally. This happens in two scenarios. In some cases, you are legally obliged to register because your business activities in that country go beyond what OSS covers. For example, if you store goods in a warehouse in Germany for sale to German consumers, those domestic sales are not part of your OSS return, so you need a German VAT registration. Once registered, you can deduct German input VAT on your regular German VAT returns, just like a local business would.

Even when not strictly required, some companies voluntarily register in a Member State where they have significant expenses. This can be useful if you regularly buy from suppliers or use services in that country. Having a local VAT number means you can claim back input VAT more directly through local returns, without relying on refund procedures that might be slower or subject to additional scrutiny.

Refund via Directive 2008/9/EC for EU businesses

If you are established in the EU but do not have a VAT registration in the Member State where you incurred expenses, you can use the electronic refund procedure set out in Directive 2008/9/EC. This is often simply referred to as the EU refund procedure.

The process works through your own tax authority. You submit a claim electronically via your home Member State’s tax portal, listing the foreign VAT you want to reclaim. Your home authority checks that you are a valid VAT taxpayer and then forwards the claim to the Member State where the expenses were incurred. That Member State reviews the application and, if the claim is accepted, refunds the VAT directly to you.

The rules of deductibility are those of the refunding Member State, so expenses must meet local conditions. There is also a firm deadline: claims must be submitted by 30 September of the year following the refund period. If the Member State takes too long to process the refund, you may be entitled to interest, but this varies by jurisdiction.

Refund procedures for non-EU businesses

For businesses established outside the EU, the route is slightly different. Instead of the EU electronic system, non-EU sellers must use the procedure set out in Directive 86/560/EEC, commonly called the 13th Directive. Each Member State administers this separately, so the process, deadlines, and documentation can vary.

Some countries require paper applications with original invoices, while others allow electronic submissions. The conditions are often stricter, and deadlines can be tight, meaning non-EU businesses must be particularly careful about planning their refund claims. In some cases, refunds are only available if there is a reciprocity agreement between the non-EU country and the Member State of refund, which can further complicate the process.

Choosing the right path

For EU-based e-commerce companies, the electronic refund procedure is usually the easiest route when no local VAT registration is required. For businesses with heavy or recurring expenses in a single country, however, local VAT registration may prove more efficient. Non-EU sellers must be prepared for a more fragmented landscape, where rules differ from one Member State to another and careful attention to national procedures is unavoidable.

The common thread is that OSS plays no role in these processes. Recovering input VAT remains entirely separate, and businesses need to plan accordingly, especially when managing cash flow across multiple markets.

Practical Recovery Pathways

Once you understand that OSS does not handle input VAT, the next step is to consider which recovery route is available for your business. The choice depends on whether you hold local VAT registrations, where your company is established, and whether your expenses are inside or outside your home country. It is worth stressing from the outset that domestic input VAT — the VAT you pay on expenses in your own Member State of identification — is always reclaimed through your regular domestic VAT return, never through OSS.

Local VAT registration and domestic returns

For many businesses, the simplest path is to register for VAT locally in the country where purchases are made. If you are obliged to register because you keep stock there, or if you choose to register voluntarily, you can reclaim input VAT directly in that country’s standard VAT return. This approach effectively treats you as a local business, applying the same rules and deadlines as domestic traders.

Some companies find this method preferable even when it is not strictly required, particularly if they have frequent or large expenses in one Member State. Having a local registration means you do not depend on refund procedures, which can take longer and sometimes involve additional scrutiny.

EU refund procedure for businesses without local registration

For EU-established businesses that are not registered in the Member State of purchase, the electronic refund procedure under Directive 2008/9/EC provides a practical alternative. You submit your claim through your home country’s online tax portal, which verifies your status and forwards the application to the Member State that issued the VAT. That country then decides whether the VAT can be refunded and pays it back directly.

The decision deadline is normally four months from submission. If the tax authority requests additional information, the period can be extended to six or even eight months. Once a decision is made, the refund must be paid within ten working days. If the payment is delayed, interest accrues, although the rate differs by Member State. For businesses with tight cash flow, these timelines are important to track. And, crucially, the claim must be filed no later than 30 September of the year following the refund period. Missing this date means losing the right to recover the VAT altogether.

National refund procedures for non-EU businesses

Businesses established outside the EU must use the national refund systems provided under the 13th Directive. Each Member State administers its own process, which can differ considerably in format, required documentation, and submission rules. In some countries, you may still need to file paper forms with original invoices, while others allow online claims. Deadlines also vary, so careful attention is essential.

A further complication is that several Member States require non-EU businesses to appoint a tax representative in order to submit a refund claim. In addition, some only grant refunds if the non-EU country in question offers reciprocal treatment to their own businesses. These conditions make the 13th Directive route more administratively heavy and sometimes uncertain.

Matching the route to your business model

The best recovery path depends on how your business operates. Sellers who run fulfilment centres or warehouses abroad often find local VAT registration unavoidable and the most efficient way to reclaim expenses. Smaller online shops with occasional costs in other Member States can usually rely on the EU refund procedure. Non-EU sellers, by contrast, must navigate a more fragmented landscape, adjusting to each country’s unique system and, in some cases, additional obligations such as appointing a tax representative.

Whichever path applies, the key point remains: OSS only simplifies output VAT. When it comes to recovering input VAT, you must work through local returns or refund procedures, each with its own deadlines and conditions.

Key Takeaways for Businesses

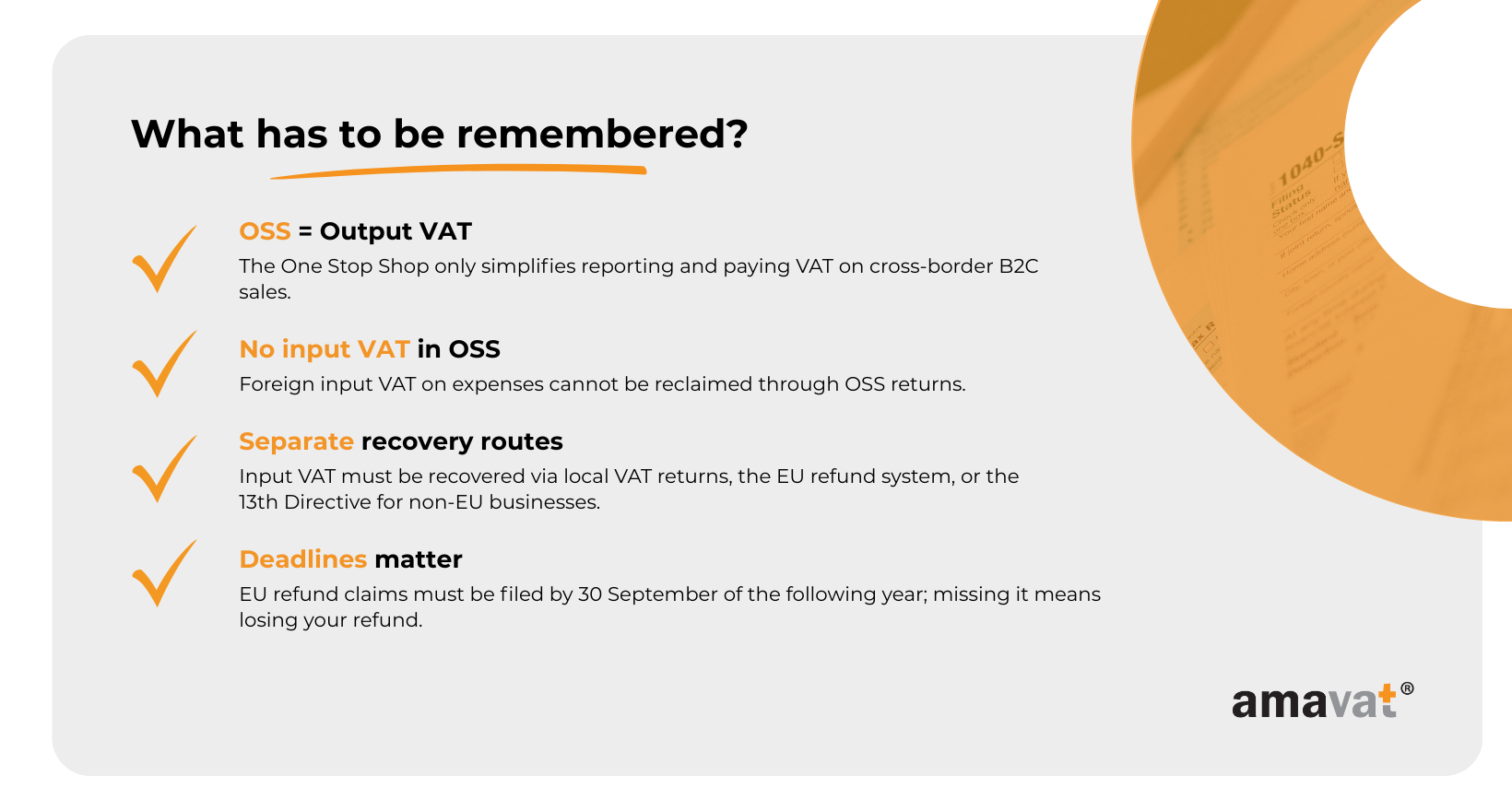

OSS is only about output VAT

The most important message to carry with you is that the OSS is a tool for simplifying the reporting and payment of output VAT, the tax you charge to consumers across borders. It does not cover input VAT, whether foreign or domestic. Your expenses — from supplier invoices abroad to logistics services — are not touched by OSS. They must be handled elsewhere.

Input VAT requires separate planning

If you pay VAT abroad, recovering it is a separate process that runs in parallel to your OSS compliance. That recovery can happen in three different ways: through a local VAT return if you are registered in the Member State of purchase, through the EU electronic refund procedure if you are an EU-established business without a local registration, or through national refund procedures if you are established outside the EU. These systems remain completely distinct from the OSS, and businesses need to plan for them alongside their sales reporting obligations.

Mapping your footprint is essential

For many small e-commerce businesses, VAT planning begins and ends with sales. But when you grow into multiple markets, the footprint of your expenses can become just as important. If you rely on warehousing services in one Member State, attend trade fairs in another, and buy stock from a supplier in a third, each of those transactions may leave input VAT on the table. Knowing where your costs fall, and which recovery mechanism applies, is essential to keeping your cash flow healthy.

In practice, this means mapping both your sales and your purchases across the EU. OSS will take care of the output VAT side, while your input VAT strategy must be built around local registrations and refund claims. By aligning these two sides of VAT compliance, you can expand your business without losing money unnecessarily to unrecovered tax.

Building VAT into your growth strategy

For young entrepreneurs scaling an online business, VAT often feels like a back-office issue. Yet, the difference between claiming or missing a refund can amount to thousands of euros each year. Thinking ahead about VAT recovery is therefore not just an administrative task but part of your growth strategy. By separating clearly what OSS does — and does not — cover, and by planning early for the recovery of foreign input VAT, you can keep your business competitive while avoiding the cash flow traps that catch out many first-time cross-border sellers.