When and how to deregister from the VAT OSS scheme?

Spis treści

It’s especially valuable if you’re running an e-commerce store shipping to several EU countries or if you offer certain cross-border services like digital downloads, streaming, or telecommunications. Without OSS, you could easily be juggling half a dozen separate VAT registrations, each with different rules and submission platforms. With OSS, all that complexity collapses into one quarterly process (for Union and Non-Union OSS). Note: the monthly cycle applies only to the separate IOSS.

But there might come a point where you need — or choose — to step away from it. Maybe your business has scaled back, and you’re no longer making cross-border consumer sales. Maybe your company has restructured, or you’re relocating your main base to another EU country, which requires you to change your Member State of identification. Depending on the move, you must update details in the same MS or be excluded from the old MS and register in the new one; it isn’t automatic. Sometimes it’s a strategic choice — you might prefer to manage VAT locally in each country for pricing, logistics, or cash flow reasons. And sometimes, unfortunately, it’s not your decision at all: if you persistently fail to comply with OSS rules, the tax authorities can remove you, leaving you locked out for two-year ‘quarantine’.

Why does deregistration matter so much? Because leaving OSS is not like cancelling a subscription or closing a social media account — it’s a legal and tax process. If you don’t follow it correctly, you could end up paying VAT twice, missing mandatory deadlines, or facing penalties that cut into your profit. Worse, your tax authority might still treat you as an active OSS user if you don’t formally deregister, meaning you could be chased for VAT returns or payments you never budgeted for. And if you’ve moved to a different EU country without correctly notifying your old one, you might be facing compliance issues in two jurisdictions at once.

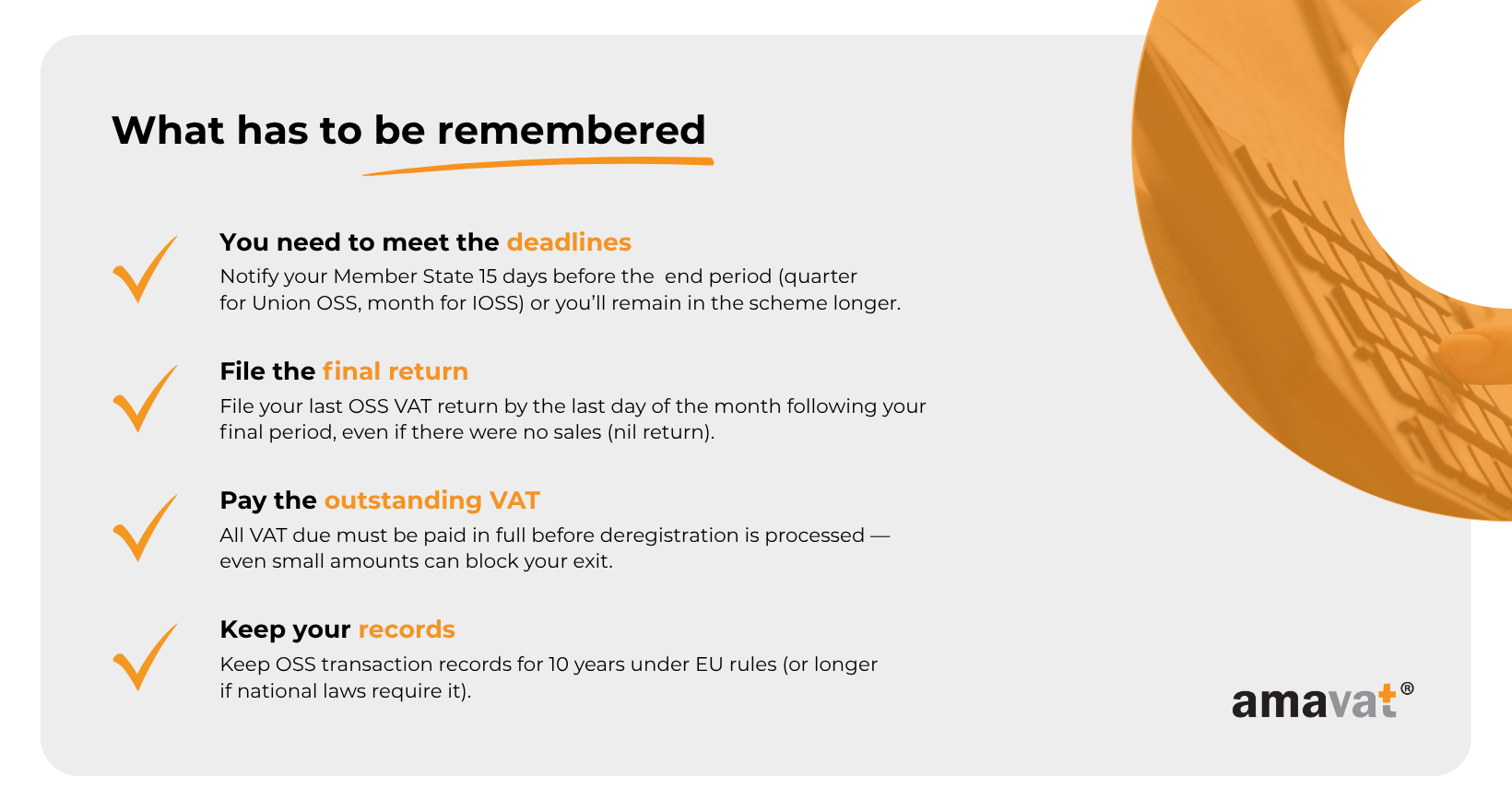

Here’s the bottom line: if you want to stop using VAT OSS, you must inform your Member State of identification at least 15 days before the end of the calendar quarter prior to the quarter in which you intend to cease using OSS (e.g., to cease from 1 July, notify by 15 June). You’ll still need to file a final OSS VAT return covering all transactions up to your exit date. Your final OSS return is still due by the last day of the month following the end of that quarter, and you must file a nil return if there were no supplies. You must also pay any VAT that’s due and keep your OSS transaction records for 10 years in case of audits.

The good news? If you voluntarily leave and later meet the conditions again, you can re-enter without delay. If you were excluded for persistent non-compliance, there’s a two-year ‘quarantine’ during which you cannot use any of the OSS/IOSS schemes.

Leaving OSS is about more than closing a chapter; it’s about closing it cleanly so you can move forward without tax complications trailing behind you. In the next sections, we’ll break down exactly when, why, and how to do it right.

When should you deregister from the VAT OSS scheme?

The VAT OSS scheme is built for businesses that regularly sell goods or certain services to consumers (B2C) in other EU countries. It’s meant to simplify your tax life, but it’s not designed to be permanent for every business. If your operations change — or if you’re no longer eligible — you may have to step out of the scheme, either by choice or because you’re required to.

Business changes triggering deregistration

One of the most common reasons to leave OSS is when you stop making cross-border sales to consumers. For example, if you used to sell handmade furniture from Spain to customers in France, Germany, and Italy, but have now scaled back to selling only within Spain, the OSS system becomes unnecessary. The same applies if you stop offering services covered by OSS, such as streaming subscriptions or downloadable software to customers in other EU countries.

If you move your place of business (or a fixed establishment) from one Member State to another, you must change your Member State of identification (MSID). Practically, you cease using OSS in the former MS and register in the new MS. Where the move triggers a change of MSID, the change is effective from the date of the move if both Member States are notified by the 10th day of the month following the change.

If you move or add a warehouse in another Member State, you’ll generally need a local VAT registration there for domestic transactions, but you still keep a single OSS registration in one MS (your MSID) for eligible B2C distance sales. Adding stock abroad does not by itself create a second OSS or force an MSID change.

These scenarios are not just bureaucratic details; failing to update your status when your business setup changes can cause serious compliance issues, especially if VAT is being misreported to the wrong country.

Voluntary deregistration

Not all departures from OSS are forced. Some businesses choose to leave voluntarily, even when they still qualify. Some B2C businesses still eligible for OSS may prefer local VAT registrations (e.g., for operational or cash-flow reasons), but this means dealing with multiple returns instead of one.

There’s no penalty for leaving voluntarily, provided you follow the correct deregistration process. However, it’s worth noting that doing so can mean more administrative work, as you’ll be dealing with multiple tax systems instead of one consolidated scheme.

Exclusion due to Non-Compliance

The least favourable reason for leaving is being excluded. If you repeatedly fail to submit OSS returns on time, don’t pay your VAT, or ignore scheme rules, your tax authority can remove you from the scheme entirely. An exclusion leads to a two-year quarantine during which you cannot use any OSS/IOSS scheme.

For example, a business that consistently misses its quarterly OSS filing dates could find itself excluded. Once out, the company would have to register for VAT separately in every country where it sells, which can be a major setback.

Handled properly, deregistration is straightforward. But leaving for the wrong reasons — or being forced out — can make life far more complicated, especially if you suddenly have to manage VAT obligations in multiple jurisdictions without the safety net of OSS. Knowing the exact triggers for deregistration means you can plan your exit carefully and on your own terms, rather than letting the tax office decide for you.

Notice periods and deadlines

Deregistering from the VAT OSS scheme isn’t something you can decide on a Friday and have wrapped up by Monday. The system is built on strict reporting periods, and if you miss the cutoff dates, you’re locked into another full reporting cycle. This is why planning ahead is so important — especially if you’re leaving because of a business change that’s already underway, like relocating or closing part of your operations.

Your exact notice period depends entirely on the type of OSS scheme you’re using. While the Union and Non-Union OSS follow quarterly schedules, the Import OSS works on a much faster, monthly cycle.

Union & Non-Union OSS

If you’re registered under the Union or Non-Union OSS, you must notify your Member State of identification no later than the 15th day of the month following the end of the previous quarter if you want deregistration to take effect at the end of the current quarter. In practice, this means your notice must reach the tax authority at least 15 days before the last day of the quarter you are leaving.

Here’s what that looks like in practice: imagine you want to stop using OSS starting from 1 July. That means you need to send your deregistration notice no later than 15 June. This is because 15 June is the last date that still allows your exit to be effective from the end of the second quarter (30 June) so that you are out from 1 July. If you miss that date by even a single day — say you submit it on 16 June — you’ll have to keep using the scheme until the next quarter starts in October.

This quarterly system can be tricky if your business changes suddenly. For example, if you close your cross-border online shop in mid-May but don’t submit the deregistration notice until June 20, you’ll still be responsible for filing and paying VAT under OSS until the end of September.

Import OSS (IOSS)

The Import OSS is even stricter because it works on monthly reporting rather than quarterly. Here, you must notify your tax authority no later than the 15th day of the month in which your final reporting period ends. Missing this means your deregistration takes effect only from the end of the following month.

For example, let’s say you want to exit the IOSS from 1 September. Your notice must be submitted by 15 September to make that happen. Miss it, and you’ll stay in the scheme until at least 1 October, regardless of whether you’ve stopped selling goods through IOSS channels.

This shorter cycle can actually work in your favour if you’re making a quick change in your business model, but it also means there’s far less room for error in planning your exit.

What happens if you miss the deadline

If you fail to meet the deadline — in either scheme — your deregistration date will automatically be set to the end of the next full reporting period (quarter for Union/Non-Union OSS, month for IOSS). This isn’t just an inconvenience; it can affect cash flow and tax planning. You’ll need to keep filing returns and paying VAT through the OSS for that extra period, even if you’ve already stopped making sales that qualify for the scheme.

For example, imagine a seasonal business that only sells cross-border from March to June. If they miss the June 15 OSS deadline, they’ll have to remain in the scheme for July, August, and September — months when they might have no sales at all but still have to submit returns.

In short, missing the notice period can tie you to OSS longer than you’d like, creating extra admin work and possibly extra costs. The safest move? Plan your deregistration date well in advance and set reminders for your scheme’s cutoff deadlines.

How to deregister from VAT OSS — Step-by-Step

Leaving the VAT OSS scheme isn’t a matter of sending a quick “thanks, but no thanks” email to your tax office. It’s a structured process with legal steps, and missing even one of them can delay your exit or create compliance issues down the line. Think of it less like cancelling a subscription and more like closing a bank account — there are forms to complete, payments to clear, and records to keep.

Identify your scheme

Before you do anything, work out exactly which OSS version you’re registered for:

- Union OSS – for EU-based businesses making B2C intra-EU distance sales of goods and/or certain B2C cross-border services to consumers in other EU countries.

- Non-Union OSS – for businesses outside the EU selling certain services to EU consumers.

- Import OSS (IOSS) – for businesses selling low-value goods imported from outside the EU directly to consumers.

Your scheme type decides how often you file returns (quarterly or monthly), what deadlines you must meet, and which online portal you’ll use for deregistration. If you’re not sure, check your registration confirmation or log into your national tax authority’s OSS portal. Misidentifying your scheme could mean you follow the wrong timetable — and that’s a fast way to miss your exit date.

Notify electronically

OSS deregistration is a fully digital process. You’ll need to log into your Member State’s official OSS or e-tax portal, find the deregistration section, and fill out an electronic notice form.

Typically, this form will ask for:

- Your business details (VAT number, contact information).

- The date you want to leave the scheme.

- Sometimes, a reason for leaving (e.g., change of business location, no longer making cross-border sales, voluntary exit).

Submitting this notice is what starts the deregistration process. Without it, even if you stop filing returns, the system will still consider you an active participant — which can lead to compliance reminders or even penalties. For Union and Non-Union OSS, this notice must be submitted at least 15 days before the end of the calendar quarter you wish to leave; for IOSS, it must be submitted at least 15 days before the end of the month you wish to leave.

File your final OSS VAT return

Your last return is a crucial step. It must include all sales and transactions covered by OSS up to your official exit date. This isn’t optional — even if your last quarter or month had zero cross-border sales, you still need to file a nil return to officially close your account. Your final return is due by the last day of the month following the end of your final reporting period, even if there are no supplies to report.

For example, if you leave on 30 June under the Union OSS, your final return will cover 1 April to 30 June. Under IOSS, leaving on 31 August means a final return for the entire month of August. Filing this final return is your way of telling the tax authority, “I’ve settled everything up to this date — I’m done.”

Pay outstanding VAT

If your final OSS return shows that you owe VAT, pay it in full before your deregistration is processed. Outstanding VAT is the number one reason deregistrations get delayed or rejected.

It’s worth noting that even a small unpaid amount — say €50 — can block your exit, keeping you tied to the scheme until the payment clears. This can mean additional returns and admin costs, so it’s better to clear everything right away.

Retain your records

Even after leaving OSS, the record-keeping obligation doesn’t go away. EU law requires you to keep all OSS transaction records for at least 10 years. These records should be detailed enough to prove correct VAT treatment if you’re audited.

This might include:

- Invoices issued to customers.

- Proof of where your customers were based.

- Payment confirmations and shipping records.

Some countries require you to keep these for even longer, so check your national rules before clearing out old files.

Changing your member state of identification

If you’re moving your place of business (or fixed establishment) to another Member State, you can’t just “transfer” your OSS registration. Merely adding a warehouse in another Member State doesn’t require an OSS MSID change, but you may need a local VAT registration there for domestic transactions.

The key here is timing: both the old and the new Member State must be notified by the 10th day of the month after the change, and the change takes effect from the date of the move if this deadline is met. This ensures there are no gaps in VAT reporting or periods of double registration. For example, if you relocate on 15 March, your notice must reach both countries by 10 April. Miss that deadline, and you could end up with overlapping obligations — or worse, unreported VAT periods.

Following this step-by-step process keeps you in control and prevents last-minute surprises. Whether you’re leaving voluntarily or because your circumstances have changed, doing it by the book ensures a clean break from OSS without extra costs or compliance headaches.

What happens after you deregister?

Once you’ve stepped out of the VAT OSS scheme, your VAT obligations don’t disappear — they just shift into a different, more fragmented system. Without OSS acting as your central reporting hub, you’ll now be dealing with multiple tax authorities, each with their own rules, deadlines, and paperwork styles. For some businesses, this is a manageable change. For others, especially smaller operations, it can mean a sharp increase in admin time and costs.

Reporting VAT without OSS

Without OSS, you must register for VAT separately in every Member State where you make B2C supplies that require VAT to be accounted for in the country of consumption. This means:

- Filing VAT returns under local laws for each country.

- Working in different languages or with translated forms.

- Following different filing schedules — some monthly, some quarterly, some annually.

Take a small online retailer based in Italy, for example. Under OSS, all EU B2C sales could be reported in one quarterly return. Without OSS, the same retailer might have to register and file in France, Germany, Spain, and the Netherlands individually, each with unique tax portals and formats. The workload multiplies quickly, and so does the potential for mistakes.

This is why voluntary deregistration should always be considered carefully. The cost of extra admin and the risk of compliance errors can outweigh the benefits of leaving OSS, especially if your cross-border B2C sales remain significant.

Immediate re-registration possibility

The good news is that if your circumstances change, you can rejoin OSS right away — as long as you meet the eligibility criteria. This is particularly useful for seasonal businesses or those testing new markets.

For example, a B2C service provider might pause cross-border operations for a year, deregister from OSS to simplify things, and then re-register instantly once they relaunch EU-wide sales. There is no waiting period for voluntary leavers, but an exclusion for persistent non-compliance triggers a mandatory two-year period in which you cannot use any OSS/IOSS scheme.

Country-Specific example — UK

Although the UK is no longer part of the EU, it operates separate VAT registration rules for cross-border sales under its post-Brexit e-commerce VAT regime (including the UK VAT Import Scheme for consignments ≤ £135).

UK deregistration from these schemes generally involves:

- Giving notice before the end of the current reporting period.

- Filing a final VAT return.

- Paying any outstanding VAT.

- Keeping transaction records for at least six years (UK rule; EU OSS requires 10 years).

While these are not part of OSS, the principles are similar — advance planning and thorough record-keeping are still essential.

Leaving OSS is not the end of your VAT responsibilities — it’s the start of a different way of managing them. The businesses that navigate this transition most successfully are those that prepare well in advance, understand each country’s VAT obligations — including whether local VAT registration is needed for warehousing or domestic supplies, which OSS never covers — and keep their paperwork in meticulous order. A clean exit from OSS means fewer headaches and a smoother path forward, whether you stay out permanently or decide to come back later.

Key resources & official guidance

If you’re planning to leave the VAT OSS scheme, the safest way to make sure you’re doing it correctly is to go straight to official sources. The EU framework keeps the rules largely consistent, but there can still be small national differences in deadlines, required forms, and how the process is carried out. These differences can catch you off guard if you rely on outdated or second-hand advice.

EU Commission VAT OSS Portal

The EU Commission’s VAT OSS portal is the main central reference for the scheme. It explains the EU-wide framework for deregistration under Union, Non-Union, and Import OSS, summarises the standard timelines for giving notice, and links to the national portals where deregistration is actually carried out. This makes it the most reliable place to confirm whether your Member State has any special rules, such as additional documentation or confirmation steps.

UK HMRC VAT E-Commerce Guidance

If you’re a UK-based business selling goods or certain services cross-border, HMRC’s guidance on the UK’s post-Brexit VAT e-commerce rules (including the Import VAT scheme for consignments ≤ £135) sets out the procedure for deregistering from those UK schemes. It walks you through the notice process, the requirement to submit a final return, and the need to settle any outstanding VAT before your deregistration can be finalised. It also reminds businesses that they must keep records for at least six years under UK rules (ten years applies to EU OSS). While the UK’s systems are not part of OSS, the approach mirrors EU best practice closely, so the process will feel familiar if you’ve dealt with OSS before.

National Tax Authority Portals

Your national tax authority’s online portal is where the actual deregistration happens — whether through a dedicated OSS section or as part of the broader VAT e-services area — depending on your Member State of identification. This is where you submit your notice to leave, file your final OSS VAT return, and check for any remaining VAT liabilities. The layout and process can vary widely between countries. For example, some systems make deregistration part of the general VAT online services, while others have a separate OSS-only process.

Using these official resources ensures you’re not just following a general guide, but the exact process your country requires, reducing the risk of delays, rejected requests, or compliance issues after you’ve left the scheme. For example, the German National tax authority portal is BZSt.

Conclusion

Deregistering from the VAT OSS scheme for reporting eligible B2C cross-border supplies is far more than ticking a box to say you’re done — it’s a formal legal process with strict timelines, defined steps, and obligations that continue long after you’ve left. Whether you’re stepping away because your business model has shifted, you’re relocating to a new base, or you simply prefer to handle VAT differently, the key is to treat the process with the same care you’d give to joining the scheme in the first place.

The essentials are straightforward: give notice within the correct deadlines for your scheme type, submit a complete and accurate final OSS VAT return, settle any VAT you still owe, and retain your records for the full ten-year period required under EU OSS rules (or longer if your country’s local VAT laws require it). Missing just one of these steps can cause delays, trigger compliance warnings, or even leave you paying VAT through OSS for longer than you intended.

Handled properly, deregistration allows you to leave the scheme cleanly, maintain a good relationship with your tax authority, and avoid unnecessary admin headaches. And because there’s no waiting period for voluntary leavers, but if you’ve been excluded for persistent non-compliance, EU rules impose a mandatory two-year period during which you cannot use any OSS/IOSS scheme, you have the flexibility to return when circumstances change and you meet the eligibility criteria again.

In the end, leaving OSS is about staying in control — making sure that deadlines, penalties, and overlooked obligations don’t dictate your next steps. By planning early, double-checking requirements, and closing every loop, you can move on from OSS with confidence and clarity. Your best bet? Just contact us and we’ll help you with everything.